More than a Lifetime Away: World Faces 100-Year Wait for Gender Parity

- According to the current trajectory for closing the gender gap across politics, economics, health and education, the overall global gender gap will close in 99.5 years

- Improvement in political representation helped narrow the overall global gender gap, even though prospects for economic opportunity have worsened in the past 12 months

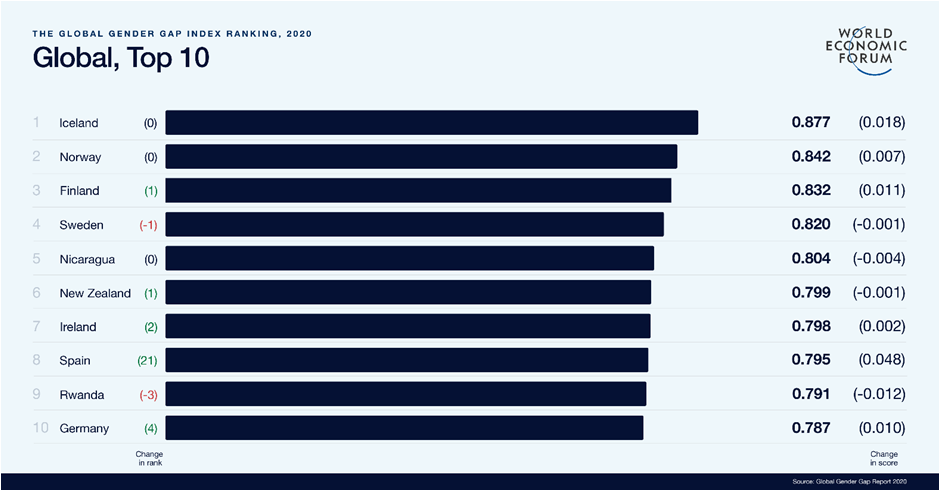

- Iceland remains the world’s most gender-equal country, followed by Norway, Finland, Sweden and Nicaragua

- Discover the full report, infographics and more information here

The time it will take to close the gender gap narrowed to 99.5 years in 2019. While an improvement on 2018 – when the gap was calculated to take 108 years to close – it still means parity between men and women across health, education, work and politics will take more than a lifetime to achieve. This is the finding of the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report 2020, published today.

According to the report, this year’s improvement can largely be ascribed to a significant increase in the number of women in politics. The political gender gap will take 95 years to close, compared to 107 years last year. Worldwide in 2019, women now hold 25.2% of parliamentary lower-house seats and 21.2% of ministerial positions, compared to 24.1% and 19% respectively last year.

Politics, however, remains the area where least progress has been made to date. With Educational Attainment and Health and Survival much closer to parity on 96.1% and 95.7% respectively, the other major battlefield is economic participation. Here, the gap widened in 2019 to 57.8% closed from 58.1% closed in 2018. Looking simply at the progress that has been made since 2006 when the World Economic Forum first began measuring the gender gap, this economic gender gap will take 257 years to close, compared to 202 years last year.

Economic Gap Widening

The report attributes the economic gender gap to a number of factors. These include stubbornly low levels of women in managerial or leadership positions, wage stagnation, labour force participation and income. Women have been hit by a triple whammy: first, they are more highly represented in many of the roles that have been hit hardest by automation, for example, retail and white-collar clerical roles.

Second, not enough women are entering those professions – often but not exclusively technology-driven – where wage growth has been the most pronounced. As a result, women in work too often find themselves in middle-low wage categories that have been stagnant since the financial crisis 10 years ago.

Third, perennial factors such as lack of care infrastructure and lack of access to capital strongly limit women’s workforce opportunities. Women spend at least twice as much time on care and voluntary work in every country where data is available, and lack of access to capital prevents women from pursuing entrepreneurial activity, another key driver of income.

“Supporting gender parity is critical to ensuring strong, cohesive and resilient societies around the world. For business, too, diversity will be an essential element to demonstrate that stakeholder capitalism is the guiding principle. This is why the World Economic Forum is working with business and government stakeholders to accelerate efforts to close the gender gap,” said Klaus Schwab, Founder and Executive Chairman of the World Economic Forum.

Could the “Role Model Effect” close the gender gap?

One positive development is the possibility that a “role model effect” may be starting to have an impact in terms of leadership and possibly also wages. For example, in eight of the top 10 countries this year, high political empowerment corresponds with high numbers of women in senior roles. Comparing changes in political empowerment from 2006 to 2019 shows that improvements in political representation occurred simultaneously with improvements in women in senior roles in the labour market.

While this is a correlation, not a causation, in OECD countries, where women have been in leadership roles for relatively longer and social norms started to change earlier, role model effects could contribute to shaping labour market outcomes.